How’s Germany doing?

I’ve written a couple of posts now on Covid-19 where I’ve mentioned that Germany is held up as a great example of success but where all-cause mortality data aren’t available. Well, now they are. On 22nd May, the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (shortened to Destatis) published all-cause mortality data. Up until then, the newspaper analyses were based on data from the Robert Koch Institute, which was only reporting Covid-specific data.

I should say that I only saw these data because they were mentioned on the excellent BBC statistics and number geek-fest that is the More or Less podcast (subscribe to enjoy a sense of balance in a wobbly world). Some of the statements about what the numbers implied were pretty strong, particularly around the impact of track and trace measures, so I was keen to see them for myself.

What do the data look like?

Let’s look at the general pattern of the data, then compare the overall statistics to the UK and Sweden. Then we’ll delve into some of the detail and see what conclusions may, or may not, be drawn. Spoiler alert: The data are very, very surprising.

The data go as far as 26th April, so they’re rather behind the England and Wales data and the Swedish data, but they are broken down by region.

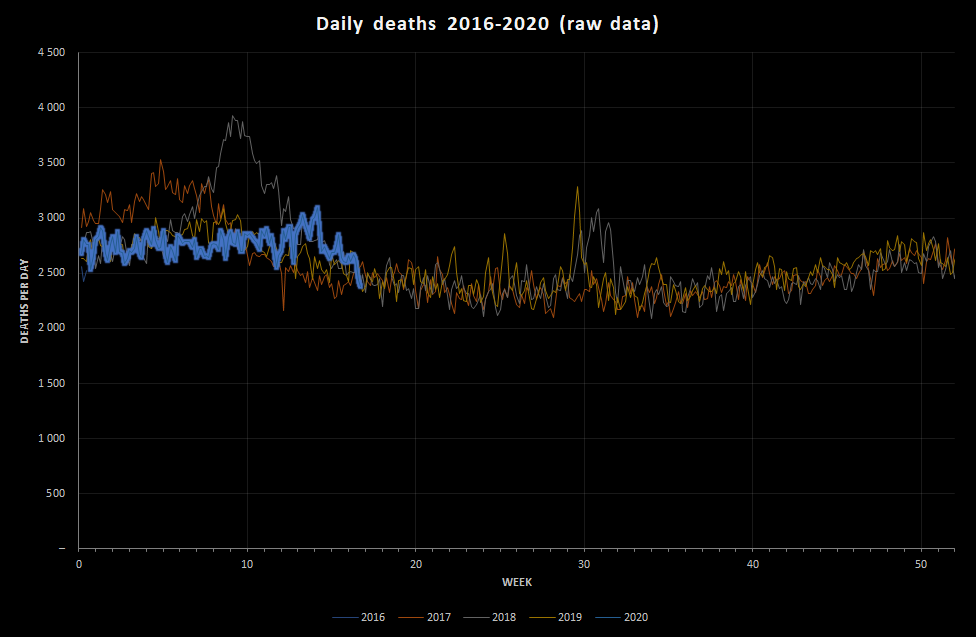

Here’s what the overall daily data look like compared to previous years. Note that the exact week numbering may be a bit variable between datasets because of leap years:

That is astounding. The data appear to show that the number of deaths in Germany in 2020 has mostly been below the average, with no discernable flu season. There is a peak that would fit with some Covid-19 events, but it’s lower than the 2018 flu peak. Is it really possible that the coronavirus pandemic has had less of an effect than seasonal flu in Germany? If so, why?

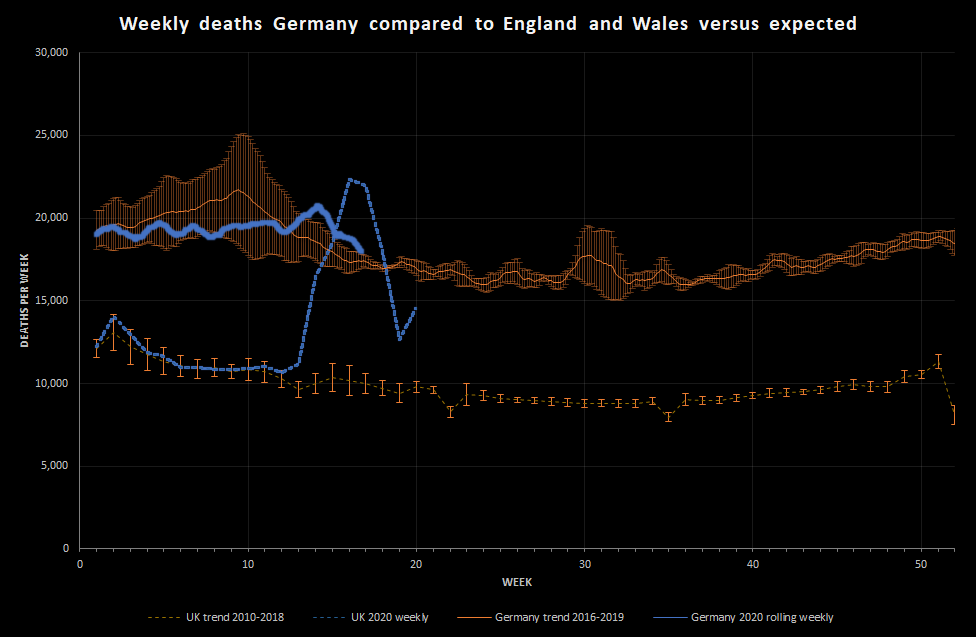

I want to put the numbers into perspective a little, so I’ve estimated the expected deaths per week based on the 2016-2019 data, and put it alongside the UK data. Note that, at this point, I haven’t scaled the results to handle the different population sizes:

This shows that, while the deaths in Germany started to rise relative to the expected value around 26th March, there wasn’t a significant excess of deaths until around 2nd April. The discrepancy between the relative size of the England and Wales peak and the Germany peak is really extraordinary.

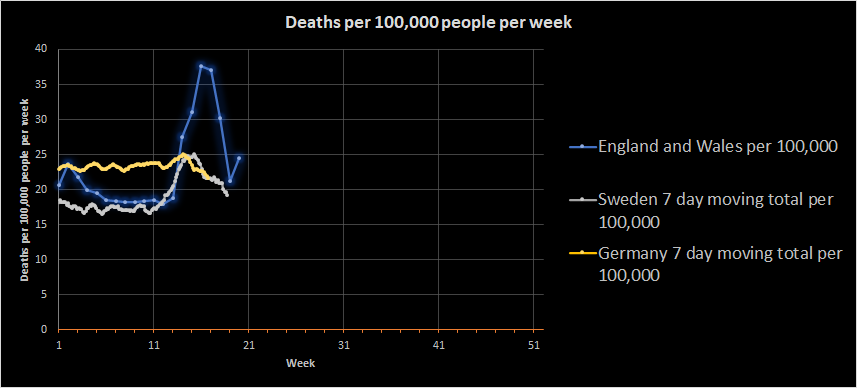

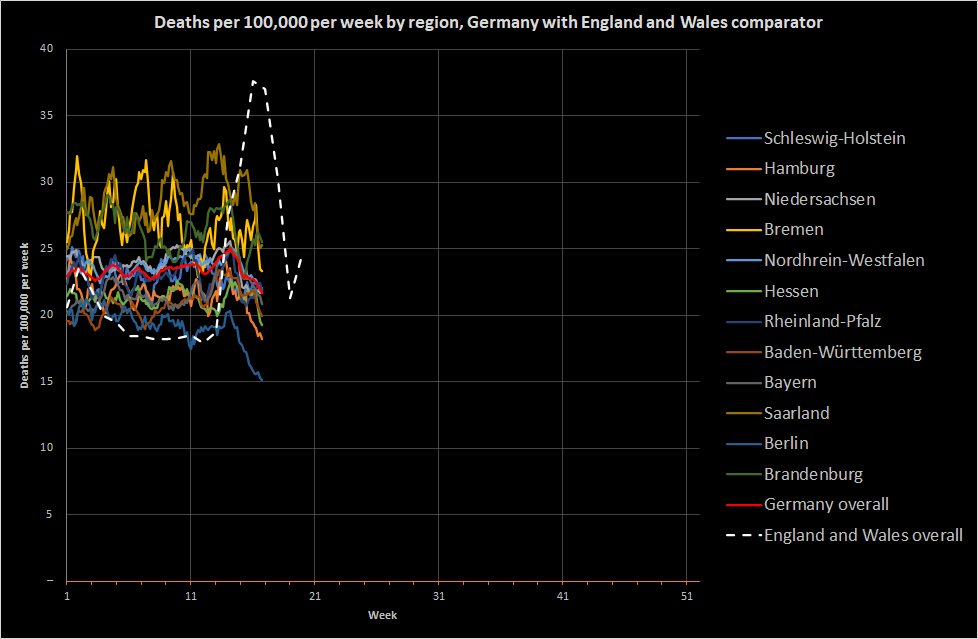

I’m going to try scaling the results now, as I did previously with the Swedish data so that we can compare the country data more directly. Destatis put the population of Germany at 82,793,800 in 2018, which compares to an England and Wales population of about 60 million and a Swedish population of about 10.5 million. This gives the following deaths per 100,000 population per week.

This casts the data in a rather different light, and one that makes me feel rather uncomfortable. The background death numbers in Germany look quite a bit higher than both England and Wales and Sweden, and that seems unlikely given that all three are wealthy nations with good healthcare provision and broadly similar demographics. My immediate assumption is that I’ve made an error somewhere, but I don’t think I have (please do correct me if you think I have).

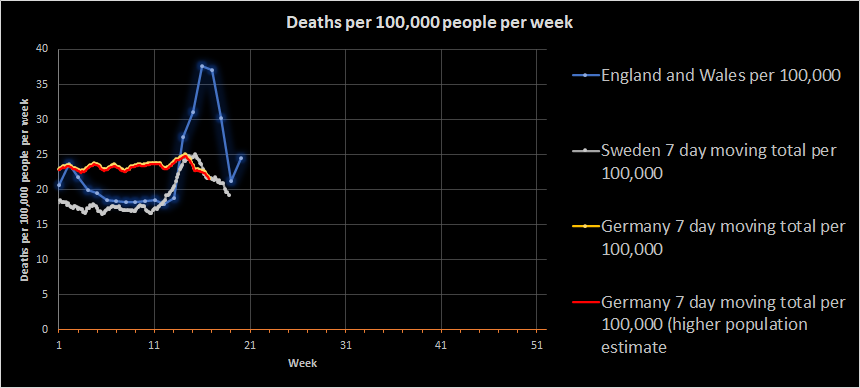

The most obvious error would be that the population size for Germany is wrong. The Destatis estimates are based on the 2011 census, which is pretty old. There is also a projected population estimate from Destatis that puts the 2020 population at 83,381,000, but that makes very little difference to the curve:

Indeed, if I take week 11 as a reasonable estimation point, the population of Germany would have to be 106.3 million for the number of deaths to be similar to England and Wales.

To try and work out what’s going on, I’m going to break the German data down by region. Destatis have provided regional data for deaths, but also some population estimates for regions, so let’s look at deaths per 100,000 per week across German regions:

As we saw in England and Wales, there are regional differences, but the regional differences in Germany are much larger overall. There may be all sorts of reasons for that, but one thing does stand out; none of the German regions show a coronavirus peak. Three regions show some pretty wild fluctuations in deaths (or at least death reporting) and also show apparently larger numbers of deaths per 100,000 (although, possibly not statistically significant):

- Bremen

- Brandenburg

- Saarland

However, none of these is obviously driving the overall apparently high number of deaths because all areas are higher than England and Wales.

I would like to look at the breakdown by age group compared to England and Wales to see if that explains the data at all, but I can’t currently find the right population statistics for Germany. I will return to this post if/when I find them.

Did Germany have an outbreak at all?

Based on the graphs above, it did. Germany appears to have had a very slight excess mortality that is likely to be attributable to coronavirus. This tallies with the data from the Robert Koch Institute, which suggest that Germany has had a large number of cases of coronavirus. Comparing countries based on disease incidence or prevalence is a real challenge because every country tests differently, but I think we have to conclude that something about Germany prevented the large peak of deaths seen in England and Wales and the more moderate peak seen in Sweden (so far, of course).

There are a number of different theories put forwards. Examples include:

- The German healthcare system is better able to cope than England and Wales

- Germany instigated a lockdown earlier in the disease spread

- Germany was better at case identification and contact tracing than other countries

Is the German healthcare system better able to cope than others?

I don’t think so. The number of deaths per week in Germany appears to be quite large. I have no idea why this is, but it is surprising. The Swedish healthcare system did not fall apart, but they still had a coronavirus peak and the England and Wales systems managed to handle a very large peak by restructuring in a very short period of time.

Did Germany lockdown faster?

This is quite a complex question because disease may arrive in different countries at different times and lockdown isn’t a single event. For example, England and Wales provided guidance on 12th March that should have restricted the movement of people showing symptoms and was advising by the 16th against all non-essential travel and requesting that people work from home where possible. The legal enforcement of a lockdown did not begin until 23rd March, but the presence of a developing outbreak was evident much earlier across the population.

Germany has a National Pandemic Plan that has been developed over a couple of decades and has included direct surveillance since at least 2001 (link in German, so my understanding is reliant on my own ropey translation skills). This involves both the Robert Koch Institute at a national level and individual Federal government. The result of this is that the details of lockdown vary slightly between regions.

In Germany, some monitoring of international travel occurred at the end of January, as it did in the UK and both countries showed a gradual increase in restrictions up to formal lockdown. A notable early event was that the German government requested that gatherings of more than 1,000 people stop on 8th March, and this appears to have been largely enforced across Germany by 10th. This was followed on 13th March by 14 out of 16 regions closing schools and nurseries. This shows the relevance of the German Federal system.

Federal regions continued to increase the severity of their local restrictions and Chancellor Merkel issued a travel warning on 16th March, but it wasn’t until 22nd March when the full national lockdown occurred.

Overall, then, Germany did lockdown faster, but not as a single nation. Local public health and government made decisions in advance of the central state. In contrast, England and Wales made decisions largely at the national level, although Wales has since diverged from England in the way lockdown has lifted.

As I stated before, the lockdown in England and Wales does appear to have helped manage the spike in deaths. I think there is a good argument that local restrictions earlier could have reduced the spread of the disease. It is, for example, understandable that some people believe the Cheltenham Festival should not have gone ahead. It’s worth remembering, though, that Sweden has had a very limited lockdown and has not, so far, experienced anything like the spike seen in the UK.

Has contact tracing helped Germany?

I don’t think the data we have available here can answer this question reliably. Evaluating the impact of contact tracing requires a lot more information than crude all-cause mortality. It is true that Germany has a well-structured and apparently well-rehearsed public health monitoring system, but so should the UK and Sweden. There are a couple of factors that may provide a clue:

- Germany had a really big flu outbreak in 2018

- The number of cases in Germany increased after lockdown was eased…or did it?

The flu outbreak in Germany in 2018 produced a peak of 26,895 deaths per week, which is about 32 deaths per 100,000 population per week. In contrast, England and Wales saw a peak of about 27 deaths per 100,000 population per week in 2015, which was our worst recent flu season. Both of these periods died down eventually, but clearly the ability to trace ill individuals did not entirely prevent flu spreading. Now, flu is different to coronavirus, but I think this indicates that, while contact tracing may have helped Germany, it is unlikely to be the sole explanation for their success.

The second clue comes from the effect of easing lockdown on the number of cases. Case estimates are imprecise and are poor for comparisons between countries, but we may reasonably expect data within the same country over time to tell us something. According to a number of reports, Germany experienced an increase in the R0 value after easing lockdown. This is not really supported by the evidence from the Koch Institute (this is the most recent data at time of writing), at least not with a high degree of confidence. What happened was that the point estimate went above 1, but there’s uncertainty around this estimate. Furthermore, the uncertainty increases as the numbers decrease because it’s more difficult to estimate. What this clue actually tells us is that robust monitoring really matters, that small outbreaks can start to cause problems if not identified, and that uncertainty is a fact of life for those making policy decisions.

From all this, I take the message that contact tracing is important. It is necessary to good control, but it is not sufficient.

What can we learn from this?

Germany is not magic. They have been fortunate so far, possibly because of the way they instituted some restrictions early through regional public health institutions working as part of a well-structured national system. Their detection and reporting systems enabled both local and national institutions to see an emerging problem and act on it. When numbers are low, the less-than-glamorous hard work of basic epidemiology can not only reduce the spread of disease, but also allow nuanced changes to public health messaging. Germany does not have an obviously superior health system to England and Wales or Sweden, at least if we use deaths as our yardstick. If I were responsible for public health in Germany, I would probably want to dig into the normal death statistics a little to understand the discrepancies between regions and the apparently high numbers (which do not reflect German life expectancy).

I think an important lesson from Sweden and Germany is the importance of credibility. In Sweden, approval for the limited lockdown measures is extremely high, in part because the public health decisions are separated from political decisions. In Germany, the Robert Koch Institute provides a central focus for a number of regional bodies. In England, Public Health England (PHE) provides this function, and it does have powers (it even has a publicly available toolkit). SARS coronavirus is on the list of notifiable conditions, and so monitoring should have occurred in England routinely, and did until the caseload became too large.

In principle PHE could have worked with local authorities to introduce restrictions by banning certain types of public gathering etc. However, PHE appears to operate through advice where possible. For example, they gave guidance to schools on managing illness in the first half of March and does not appear to be comfortable enacting more draconian rules. Giving advice seemed to work quite well in Sweden, but it depended on the right people having a sufficiently loud voice to be heard by the population and a sufficient level of credibility to encourage them to follow it. I’m not sure PHE has that voice, and it can struggle to be heard by the population against the louder voice of the NHS. That may be unfair, but I think the key messages from the evidence I’ve seen are:

- Outbreaks of illness will happen even if you have surveillance systems, and they even happen in Germany

- Routine outbreaks are managed well by existing systems in many countries, but the systems can fail

- England and Wales suffered from a very rapid rise in cases and associated mortality, and the causes of this are not obvious

- Lockdown works, but lockdown is not one thing. It can take multiple forms

- Contact tracing works, when the caseload is manageable

- Coronavirus will return severely unless it is managed very carefully

- Having robust systems for disease surveillance is a requirement for good disease control and allows for adjustments in restrictions to freedom

- Basic epidemiology, hygiene, and good self-care are the most powerful tools we have against life-limiting disease

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.