Do healthy people die of Covid-19?

I’ve been asked to write this because this question is one of the most commonly asked on Google, so lots of us have questions about our risk. We’re entering a phase of disease management where it is difficult to balance the ongoing need to have some restrictions with the impacts of drastic restrictions on public freedoms. I think people feel pulled in multiple directions, and there’s a real danger of nuanced discussion being replaced by people shouting on either side of an unnecessary argument.

For those of you too busy to read the rest, yes, otherwise healthy people do die of Covid-19. The current risk, in the UK at least, for any particular individual is very low, so there is no need to panic. However, deaths do happen. As with many illnesses, a healthy lifestyle and precautions (e.g. hygiene and managing exposure) are likely to help you reduce your individual risk. The greatest risk, by far, is societal, and basic public health measures (outbreak containment, biosecurity around the vulnerable, and measures to reduce population transmission) remain the best means of limiting the impact of the illness. The reason for this is that individual risk consists of the risk of catching Covid-19 multiplied by the individual risk of death if you do get Covid-19. This means that the simplest way to reduce risk overall is to reduce the spread of virus.

The aim of this post is to provide you with enough information to understand the risk objectively, so you can make informed decisions. The best thing is, you don’t have to believe me. As with all the Covid-19 posts, I’ll share where I’ve got data from so that you can analyse it yourself if you want to and update your knowledge as new information becomes available.

Healthy people can die of Covid-19, but that doesn’t mean it’s likely

The question posed in this article is superficially simple. All I have to do is provide one example of a person who was healthy (apart from having Covid-19) who died to prove that healthy people can die of Covid-19. Here goes:

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have, like most national health bodies, been tracking Covid-19 illness for some time. Pretty early on, they analysed data on hospitalisations and deaths to understand the effect of comorbidity (i.e. other illnesses) on the risk of death. Back in April, they observed that approximately 1 in 5 people in intensive care with Covid-19 had no underlying health condition (based on a specified list of risk conditions). Of those who died, 6% had no underlying condition.

You probably had an immediate, visceral, reaction to that information. It may have been, “Wow, that’s more than I thought”. It may have been, “I bet those 6% were overweight”. Whatever your immediate response, write it down so that you can think about it later.

The data and discussion that follows is not to prove you right or wrong, it is to allow you to think things through rationally and understand why other perspectives may differ.

Healthy people can die of Covid-19. However, knowing that some healthy people could die is not the same as understanding real risk. I could be hit on the head by an asteroid, but it’s not something I worry about. I also don’t worry a lot about my personal risk of Covid-19 because I know my personal risk is low. I do worry that people I care about will die and I worry about the impact of the pandemic and the control measures on normal life because those are real, tangible, risks, and they’re actually quite big.

Our risk of death depends on our risk of catching SARS-CoV-2 and the consequences of infection

To understand complex risks, it can help to break them down. To die from Covid-19 I have to catch it, show symptoms, progress to a severe illness, and die. That’s too complex for my simple brain, so I’m going to reduce it to: I have to have the virus, I have to show symptoms, and I have to die.

Let’s start with the risk of catching it. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) in England and Wales is conducting sampling studies of the population to estimate how many people have SARS-CoV-2, regardless of symptoms, in the general population. Obviously, this changes over time and depends on how well controlled the epidemic is.

If we assume that I was at home and not already hospitalised with illness, the ONS analysis suggests that my chance of having SARS-CoV-2 between 7th-13th August was roughly between 1 in 3,200 to 1 in 1,600 (0.03-0.06 percent). Another way to express this is to say that, for every 100,000 people at home, somewhere between 31 and 63 had SARS-CoV-2. This varies by region, with it being more like 70 per 100,000 in the North West.

Not everyone who has SARS-CoV-2 develops the symptoms of Covid-19, and not everyone seeks treatment (or diagnosis). For a lot of us, what we really think about is the risk of dying if we know we have Covid-19. While people weren’t routinely tested at the beginning of the epidemic in the UK, it is available for most people now. The UK government provides data on the number of identified cases per week for Covid-19. This includes pillar 1 (hospital and Public Health England labs) and pillar 2 (general population) data. For 7th-13th August, the number of positive tests was 6,418 (701 pillar 1 and 5717 pillar 2). This is English data, and so equates to a population of around 56.3 million. This gives a rate of approximately 11 cases per 100,000 population per week, which is an individual risk of around 0.01 percent per week.

I’m going to assume that all the people who die of Covid-19 are in that 0.01 percent per week, because those are the ones that are more likely to be showing symptoms. That may be an inaccurate assumption, but I think it works for this situation now national testing is up and running.

Okay, the risk of me dying in that week then is the probability of me having Covid-19 symptoms (0.01 percent per week) multiplied by the risk of death for people with Covid-19 symptoms. There were, according to ONS statistics 152 deaths in England and Wales in that week where Covid was recorded on the death certificate. While deaths are likely to occur some time after diagnosis, the number of deaths is reasonably stable at the moment, so that gives us a risk of death of around 152/6,418. This is around 2.4 percent. In reality, the number of deaths will be higher, and we have already seen that the number of cases is higher. However, if we are talking about healthy people, the risk of Covid interacting with other illnesses is removed, so it’s a reasonable starting point.

This means that, if I had to guess the risk of death from Covid-19 in the next week for a random person, I’d guess it was something like 0.01 percent x 2.4 percent, which is around 0.00024 percent per week. To provide some comparison for that, the ONS data show 8,945 deaths from all causes in the same week. That gives a risk of death of around 0.015 percent per week, meaning that I’m much more likely to die of something else rather than Covid. That’s why my own mortality isn’t something I’m worrying about at the moment.

I could have calculated this directly by saying that the population of England and Wales is 59 million and there were 152 confirmed Covid-19 deaths in that week giving 0.00027 percent. The slight discrepancy is because I’m using England data to calculate England and Wales results, but the difference is tiny. However, the reason I’ve split the calculation up is to show you what’s driving it. Without knowing anything about a person, I’d guess that their risk of death when they have a confirmed Covid-19 diagnosis is about 2.4 percent. Your personal risk is almost certainly not 2.4 percent. Let’s have a think about what it could be.

When cases are low, even the vulnerable are at low risk

The CDC data I started this article with included 4,470 Covid patients with no pre-existing conditions. Of these 11 died, giving a risk of approximately 0.25 percent. If I assume this all happens in a single week and plug it into my calculation above, I get a risk of death of around 0.000025 percent per week. This is about a tenth of the average weekly risk, but both risks are tiny. Essentially, healthy people have an even more tiny risk of dying than average.

What about seriously bad health?

Well, one of the highest estimates of risk came from a paper by Zhang et al. looking back at 28 cancer patients with Covid-19. This group observed 8 deaths, giving a risk of 28.6 percent. This is very likely to be an over-estimate for general cancer patients as the sample size is very small and subsequent studies with more patients show lower numbers. For example, Miyashita et al. looked at electronic hospital records in New York and observed 334 cancer patients with Covid-19, of whom 37 died (11.1 percent). Even that is likely to be an over-estimate for a general cancer patient living in the community, but it sounds scary. It doesn’t have to be.

If we take these estimates and say that the true risk is somewhere between 10 and 30 percent, the risk of catching Covid-19 and dying as a cancer patient currently looks like being between 0.001 and 0.003 percent per week, which is between 1 and 3 deaths per 100,000 people per week. That is still quite a low number.

If cases increase, the vulnerable bear the brunt of it

We’ve seen that our individual weekly risk can be crudely estimated as the product of the risk of catching Covid-19 and the risk of dying if we have Covid-19. We’ve also seen that the low rate of Covid-19 keeps risk low, even if we are in a high-risk group. This is fairly obvious when you think about it.

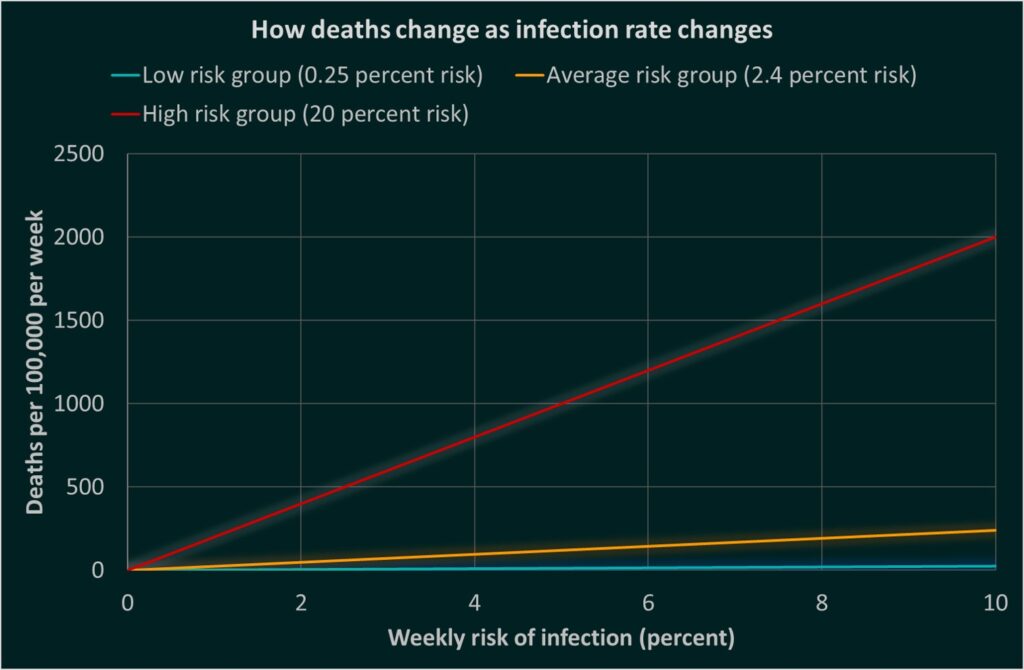

It follows, then, that the risk of death increases if the number of cases increases. What may not be obvious is that, as the risk of infection increases, the gaps between the high- and low-risk groups would be expected to grow:

I need to make a point here: We wouldn’t do formal statistical modelling of risk quite like this. We would probably use a formal survival model and describe the effect of different risk factors using the logarithms of ratios of hazards or odds within the model. All this would help give more reliable estimates with measured uncertainty. The thing is, you don’t need to do very complicated statistics to get an idea of what is driving your risk. In this case, you have two main components to the risk. Using simple multiplication, you can get a very rough estimate of the general size of a risk and, more importantly, you can see what is driving risk. In this case, you can see how the drivers of risk help tell you what to do.

Keep yourself safe

Based on this simple analysis, you probably want to do two things personally:

- Put yourself in the lowest risk group you can do

- Keep your risk of exposure low, particularly if you are vulnerable

Protect others

Telling people with serious illness to isolate themselves is a very hard thing, particularly if those people have a limited life expectancy already. While the general risk of infection is low, we all have a low risk of death. Therefore, it is in the interests of society as a whole to reduce infection risk.

Look at the difference between the survey-based estimate of infection from the ONS and the number of confirmed cases from PHE. The ONS estimated that the current risk of infection was around 0.045 percent per week (between 0.03 and 0.06 percent). PHE identified about 0.01 percent of the population per week as being infected. These are low risks, but they occur in clusters. If you have been in contact with a person with a confirmed diagnosis, you really must isolate and get tested because over two thirds of cases are not formally diagnosed so testing alone cannot prevent disease spread. Principally, this is because a lot of people won’t show symptoms.

I haven’t talked about long-term health effects of illness in healthy people because we don’t really know what they look like yet and, if you protect yourself from death you also protect yourself from long-term health impacts. Which is obviously a good thing.

What is a healthy person?

Finally, I want to go back to the CDC data. If you want to reduce your personal risk from Covid-19, you probably want to know what the main risk factors are. Sadly, we don’t really know, but we can guess, and the CDC data can help us.

Broadly speaking, if a disease is seen more frequently in more severe patients, it’s probably indicating that the disease is a risk for more severe illness. This isn’t totally reliable because illnesses tend to cluster (i.e. one person may have multiple conditions) and other hidden variables (such as age) may be associated with both risk and illness. It’s also difficult to use it to assess the risk of rare conditions. Nevertheless, it may be helpful.

The table is available in the full CDC report here. From this, it is clear that diabetes mellitus is likely to be associated with an increased severity of illness. Overall, 10.9% of the sample had diabetes, but only 6% of the non-hospitalised patients did, while 32% of the ICU patients did. The majority of these patients will have type II diabetes, so it is not clear if type I diabetes (which people are often born with) is also associated with an increased risk. Similarly, cardiovascular conditions increase risk. In contrast, the proportion of people with no existing conditions drops dramatically across the severity spectrum.

Based on this, if you are in a position where you can improve your general health, you should. This is very different from claiming that only people with pre-existing conditions die.

We are all at risk of motivated reasoning, where we tend to find arguments and adjust our own arguments to support what we want to be true, rather than what is true. Returning to that note you made at the beginning of this article; If you just thought to yourself, ‘Ah, but I bet a lot of those apparently healthy people were obese’, you may be experiencing motivated reasoning. Here’s why.

According to the latest NHS Health Survey, in England 43% of adults have at least one long-standing medical condition, and 56% were at increased risk of chronic disease because of their BMI and waist circumference. These are not people we would expect to die any time soon, they are just people. They are us. If you dismiss Covid-19 as being unimportant because it only affects ill people, you are very wrong. About half the population have a pre-existing health condition, and most of us would not expect them to die any time soon.

If you thought, ‘Wow, 6% is quite high’, please remember that your absolute risk if you are healthy is still very small. 50% to 60% of the population have no underlying condition, so you’d expect more. The fact that the percentage is down to 6% by the time we’re looking at deaths actually shows that good health is a very powerful protective factor.

If you are the perfect weight with no other health conditions, you exercise daily and eat nutritious and healthy food, you may be at a very low risk of dying from Covid-19 if you get it. At each stage of illness, the more healthy you are, the better your chances, so you should keep yourself healthy. Being seriously ill is a physical challenge. The fitter you are, the better your chance of handling that challenge. The fewer the number of cases in your area, the lower your chance of catching it in the first place, and the lower the chance of other vulnerable people catching it, so keep fit and protect your community. It’s that simple.

We’re probably getting better at testing

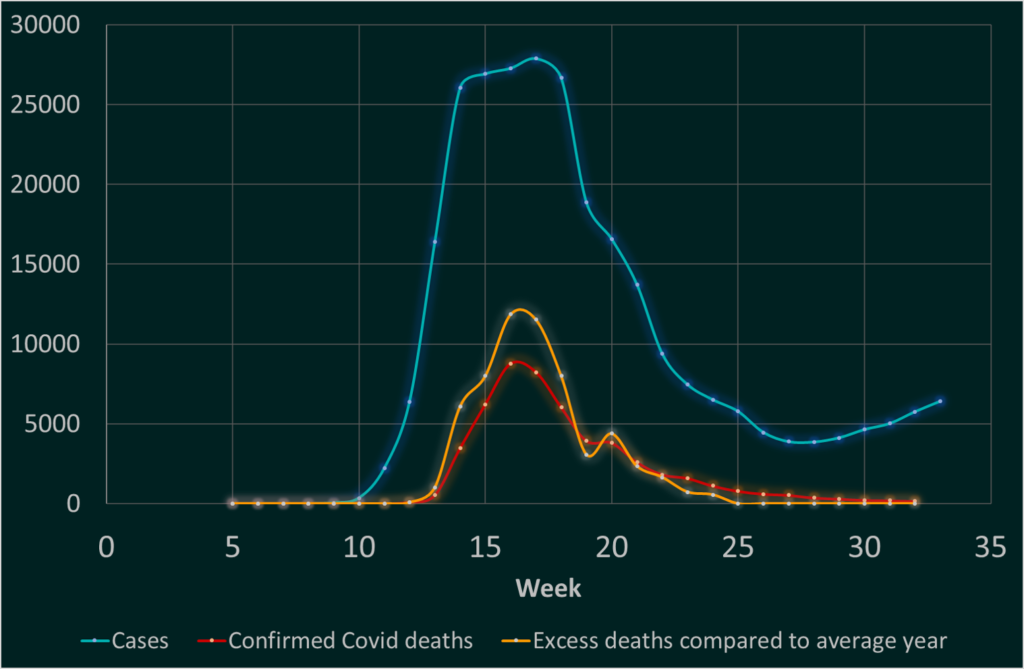

This post is a bit wordy, so here’s a picture:

As we get better and handling this pandemic, we should expect to see the number of cases identified through opportunistic testing increase, hopefully with the ONS estimates from population sampling remaining steady or declining. This would indicate population identification and management improving and us identifying a greater proportion of those with illness. If we’re doing this, we should be capturing more of the infected people with relatively mild illness. This means that the death rate from illness will appear to decline. A greater proportion of the positive tests will be among the young and healthy, because we are capturing minor illness better. This is a good thing because it indicates that we are getting on top of local clusters of illness. It does not, necessarily, mean that young people are being careless.

Now look at the graph again. There may be some cause for hope. Not complacency, but hope. Time will tell.